Exploring the Impact of Black Spending Power on America's Economy.

- Al Lloyd

- Sep 27, 2025

- 8 min read

2 trillion dollars from 14% Black Americans, where is the money? This article expands on what consumers spend it on.

Black buying power in the United States has been on a steady rise. In 2019, it was reported at $1.4 trillion and is expected to grow to $1.8 trillion by year-end of 2024. Additionally, the Selig Center for Economic Growth estimated that African American buying power reached $1.6 trillion, accounting for 9% of the nation's total buying power. While specific projections for 2025 are limited, these trends suggest a continued increase in Black buying power, potentially surpassing $1.8 trillion by that year.

The Black buying power in the U.S. is projected to reach approximately $1.98 trillion by the end of 2025, reflecting a steady increase that underscores the economic influence of the Black community. And expected to reach anywhere from $2.5 trillion to $3 trillion by 2030. This growing financial strength is part of a broader trend observed over recent decades, as the Black population has not only grown but also gained greater access to education, higher-paying jobs, and entrepreneurship opportunities. However, the full impact of this buying power depends on where and how it is spent, with ongoing efforts to direct more dollars toward Black-owned businesses to strengthen community wealth.

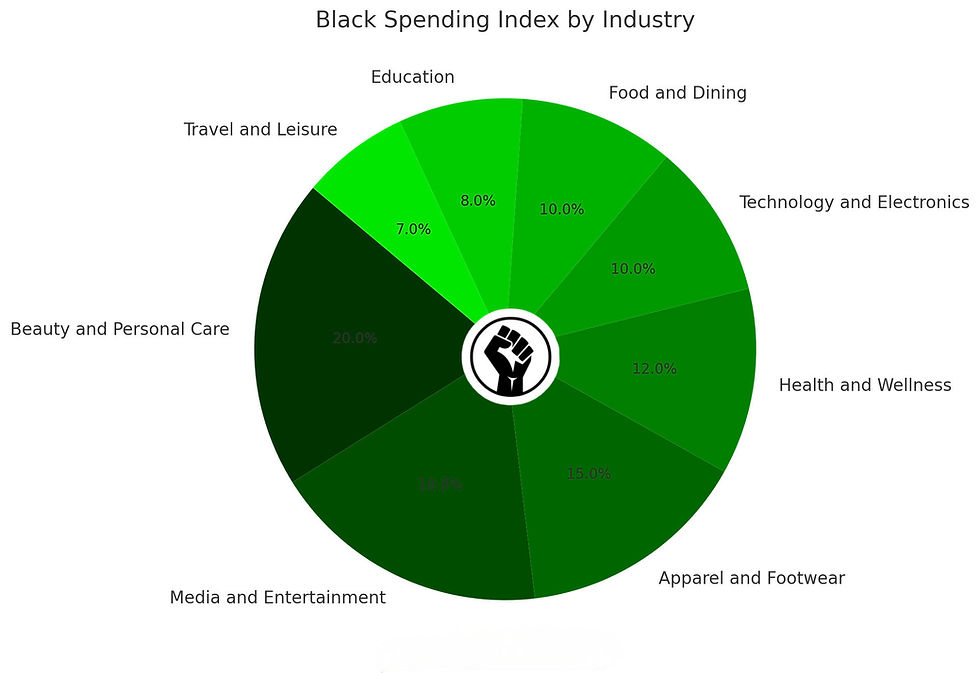

The beauty and personal care industry remains one of the sectors most significantly shaped by Black consumer spending. Black Americans are trendsetters in haircare, skincare, and cosmetics, collectively spending billions each year and influencing global markets. Despite representing a smaller percentage of the U.S. population, Black consumers account for a disproportionate share of spending in these categories. This has prompted major corporations to adjust their product offerings, marketing strategies, and even their corporate policies to cater to the needs and preferences of Black consumers.

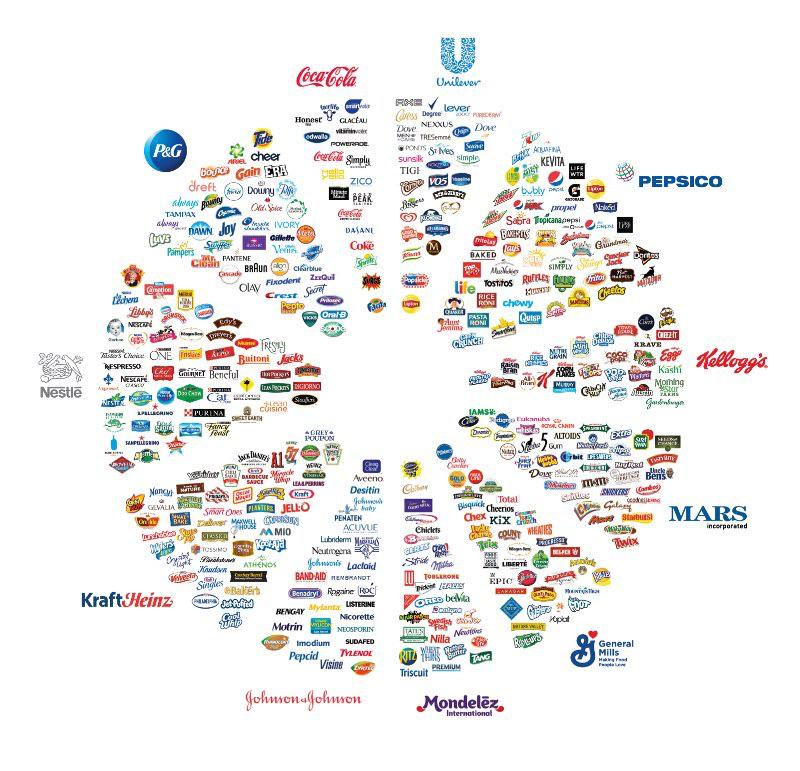

Another major area of influence is media and entertainment. Black Americans are leading consumers of streaming services, music, and television, with a cultural influence that far exceeds their population size. Streaming platforms like Netflix, Hulu, and Spotify have increasingly incorporated Black-led productions and curated content to appeal to this audience. Black consumers also dominate spending in digital content, gaming, and social media engagement, making them a coveted demographic for advertisers and content creators. Ironically these companies are large monopolies like LMVH, P&G, Nestle and many more

The fashion industry also benefits significantly from Black spending power. Black consumers are key drivers of trends in footwear, apparel, and accessories, often dictating styles that later become mainstream. Designer brands, athletic wear companies, and luxury labels have increasingly recognized the importance of the Black demographic, not only for their direct spending but also for their cultural influence on global fashion trends. From streetwear to high fashion, the impact of Black consumers is evident.

Despite these gains, many advocates point to the disparities in how this buying power is distributed and leveraged. The vast majority of Black consumer dollars are spent outside of the Black community, which limits the economic benefits for Black-owned businesses and families. Studies show that money circulates within Black communities far less frequently than it does in others, such as Asian and Jewish communities, where dollars are reinvested multiple times before leaving. This disparity underscores the need for intentional spending to build lasting wealth.

The importance of supporting Black-owned businesses has gained momentum, particularly in recent years, with campaigns such as Buy Black and initiatives tied to movements for racial equity. Online directories, apps, and social media campaigns now make it easier than ever for consumers to identify and support Black entrepreneurs. Investing in these businesses not only empowers individual entrepreneurs but also creates jobs and fosters generational wealth within the community.

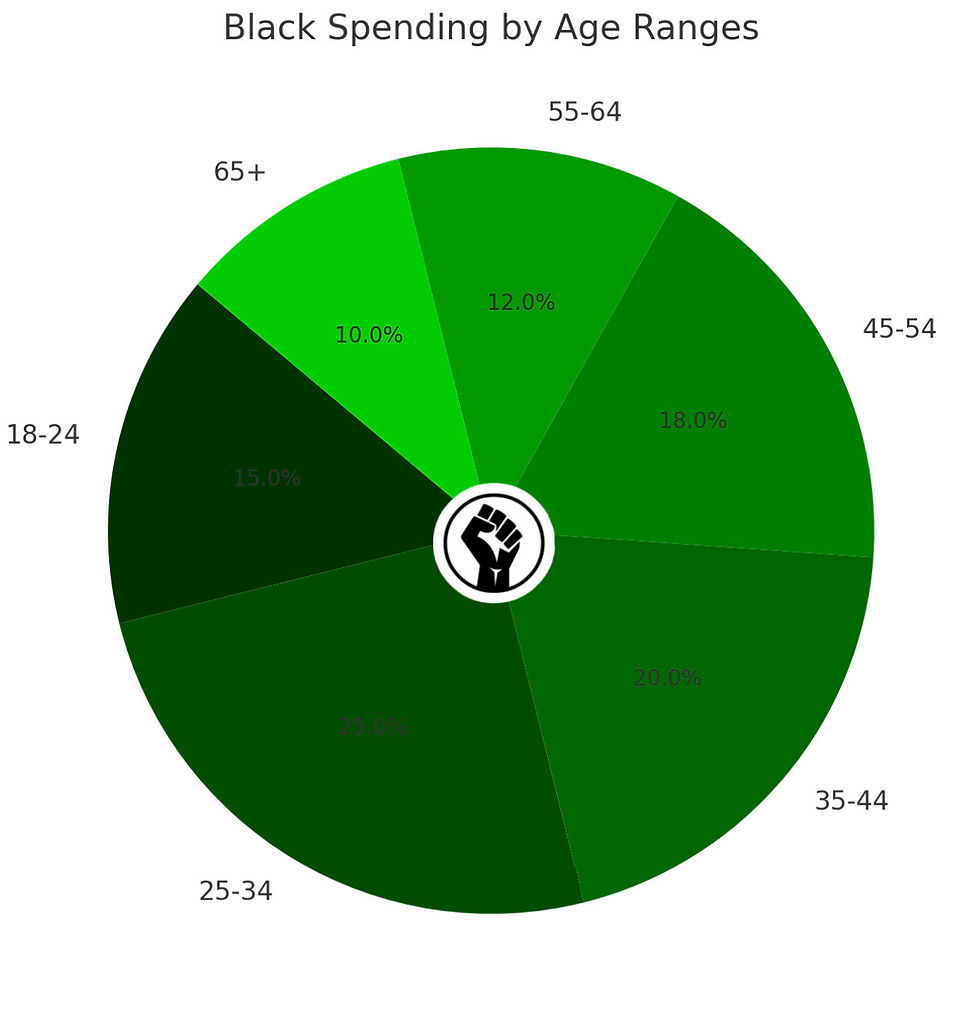

18-24 years old (15%): Young adults in this range often prioritize spending on education, technology, and personal interests such as entertainment and fashion. Their disposable income tends to be lower as they are often in college or starting their careers, but they are major contributors to trends in digital content and fast fashion. However, they are the leading group in debtors from student loans, credit card loans, and business loans.

25-34 years old (25%): This group represents the largest share of spending, driven by individuals in their prime working years. They often focus on housing, travel, and upgrading lifestyle products, such as home furnishings, automobiles, and tech devices. Many in this range are also starting families, increasing expenditures on childcare and family-related services.

35-44 years old (20%): Consumers in this range tend to focus on family-related spending, including education, homeownership, and healthcare. They are also significant contributors to industries like food, dining, and travel, as they balance professional and personal commitments.

45-54 years old (18%): Often in peak earning years, this group spends heavily on healthcare, saving for retirement, and supporting older children in higher education or launching their own careers. They also maintain strong spending on leisure, including travel and hobbies.

55-64 years old (12%): Nearing retirement, individuals in this age group often shift their focus to healthcare and wellness, as well as financial planning for retirement. Their discretionary spending may also include travel and recreational activities, reflecting a "reward yourself" mindset after years of work.

65 years old and up (10%): Spending in this age range tends to prioritize healthcare and essentials. Many in this group live on fixed incomes, but they also allocate funds for leisure, travel, and supporting younger family members, such as grandchildren. This detailed breakdown highlights how spending priorities evolve with age, influenced by life stage, income, and familial responsibilities. It also underscores the importance of targeting marketing and business strategies to these distinct demographics, as each group shapes specific sectors of the economy.

Education and workforce development also play a critical role in the growth of Black buying power. The rising number of Black Americans earning college degrees and entering higher-paying professions is directly tied to their increased economic influence. However, wage gaps and systemic barriers still limit the full potential of Black income growth, highlighting the need for policies and programs that address equity in hiring, pay, and promotion opportunities.

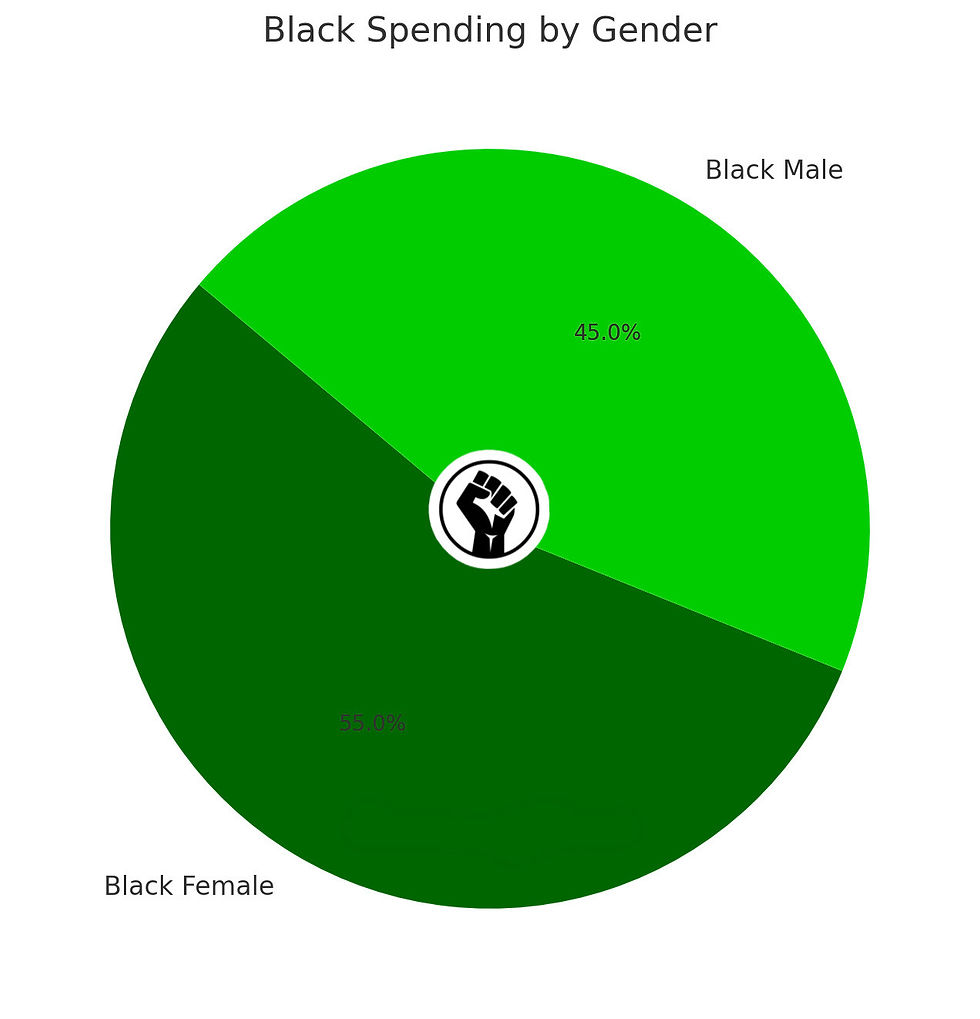

Entrepreneurship is another driving force behind the growth of Black buying power. Black women, in particular, are leading in business formation, with startups ranging from tech firms to health and wellness companies. Despite facing challenges in accessing capital, these entrepreneurs are transforming industries and creating new pathways for economic mobility. Support for Black entrepreneurship through funding, mentorship, and partnerships is crucial to sustaining this growth.

While the projected $1.98 trillion buying power figure is impressive, it also calls attention to the need for strategic action. Economic empowerment advocates emphasize the importance of financial literacy, community investment, and wealth-building strategies to maximize the impact of this spending. Without these efforts, much of the potential economic benefit could continue to flow out of Black communities.

Ultimately, the growth in Black buying power is a testament to the resilience and resourcefulness of Black Americans in the face of systemic challenges. While significant progress has been made, much work remains to ensure that this economic influence translates into lasting prosperity and equity. By prioritizing intentional spending, investment in education, and support for Black-owned businesses, the Black community can leverage this buying power to drive broader social and economic change.

These districts are designed to emulate the success of the historic Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma—once known as "Black Wall Street"—which thrived in the early 20th century as a hub of Black-owned businesses and financial independence.

The Greenwood District was a remarkable example of a self-sustaining Black economy during the early 20th century. In its heyday, Greenwood was more than just a neighborhood; it was a vibrant ecosystem where the recirculation of Black dollars created unparalleled economic strength and resilience within the community. Nearly every dollar earned within Greenwood stayed within the district, supporting a network of Black-owned businesses, professionals, and laborers, thereby creating a self-contained economic stronghold.

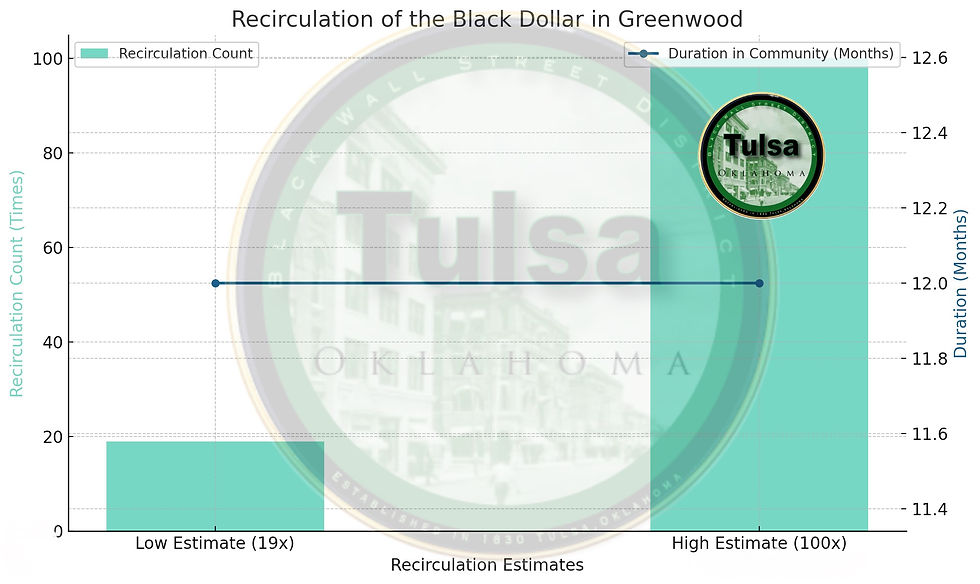

The power of recirculation of the Black dollar in Greenwood was extraordinary by any standard. Historians and economists estimate that each dollar earned in the neighborhood changed hands 19 to 100 times within Greenwood before leaving the community

Remarkably, it is believed that the money stayed in North Tulsa for over a year before being spent elsewhere. This dynamic underscored the symbiotic relationships between Greenwood’s residents, merchants, and service providers.

The neighborhood housed a diverse range of Black-owned businesses, including grocery stores, theaters, pharmacies, restaurants, and hotels. For example, John and Loula Williams, prominent business owners, established the Dreamland Theater, which drew customers and entertainers from across the country. These establishments ensured that residents had access to nearly every good or service they needed within their own community, further reinforcing the circulation of wealth locally.

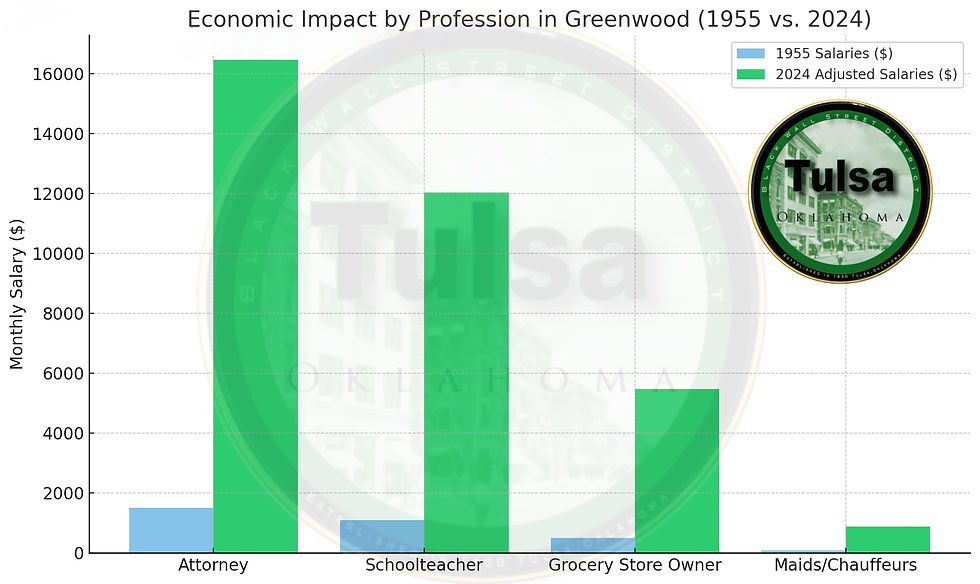

By the mid-20th century, Greenwood’s economy was still thriving, with salaries for Black professionals and workers reflecting a wide range of earnings:

Attorneys earned $1,500 per month in 1955, equivalent to approximately $15,987 in 2024 when adjusted for inflation. Schoolteachers, a backbone of the community, made $1,100 monthly, translating to about $11,589 in 2024 dollars. Grocery store owners, who played a critical role in keeping money circulating locally, earned $500 a month, or around $5,500 in today’s terms. Maids and chauffeurs, often employed by wealthier residents of Greenwood, earned between $80 and $100 monthly, roughly $850 to $1,500 when adjusted for inflation. These figures reveal that Greenwood supported a range of incomes, with opportunities for economic mobility. Professionals lawyers like, B.C. Franklin and teachers had middle-class salaries, while entrepreneurs contributed significantly to local wealth creation by reinvesting their profits back into the community.

The success of Greenwood’s economic model was driven by four key factors:

Strong Community Cohesion: The sense of unity and mutual support within Greenwood ensured that residents consciously chose to patronize local businesses, even when doing so might have been less convenient or more expensive than seeking goods and services outside the neighborhood.

Entrepreneurial Spirit: Greenwood was a hub for Black entrepreneurship, with business owners striving to create not just livelihoods for themselves but also opportunities for their neighbors. This entrepreneurial culture fostered economic independence and innovation.

Limited Access to Outside Markets: During segregation, systemic racism barred Black residents from accessing many businesses and services outside their community. While this was a form of exclusion, it inadvertently reinforced Greenwood’s self-reliance, as residents had little choice but to support one another.

Wealth Multiplication Through Circulation: Each transaction in Greenwood—whether between a barber and a teacher or a lawyer and a restaurateur—multiplied the wealth circulating within the community. This continuous exchange amplified the collective prosperity of the district.

The Greenwood neighborhood’s success in the recirculation of the Black dollar offers a powerful lesson on the potential of community-focused economics. Its economic model highlighted how localized spending and reinvestment can generate wealth, foster entrepreneurship, and empower communities, even in the face of systemic discrimination. Though the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre tragically disrupted Greenwood’s prosperity, its legacy continues to inspire contemporary movements aimed at building Black economic power.

Today, advocates for economic justice often point to Greenwood as an example of what is possible when communities prioritize supporting local businesses and circulating wealth within their own networks. Programs aimed at fostering Black entrepreneurship, such as local incubators and cooperative economic models, draw heavily from Greenwood’s example.

Greenwood’s story is a testament to the power of intentional economic practices and the resilience of a community that chose to uplift itself through mutual support and shared prosperity. While external forces ultimately challenged its longevity, the success of the recirculation of the Black dollar in Greenwood remains a shining example of what can be achieved through collective effort, entrepreneurship, and community solidarity.

Sources:

Comments